- Home

- Gaute Heivoll

Across the China Sea

Across the China Sea Read online

ACROSS THE CHINA SEA

Also available in English by Gaute Heivoll

Before I Burn

ACROSS THE CHINA SEA

A Novel

Gaute Heivoll

Translated from the Norwegian by Nadia Christensen

Graywolf Press

Copyright © 2013 by Tiden Norsk Forlag, Oslo. First published under the title Over Det Kinesiske Hav.

English translation copyright © 2017 by Nadia Christensen

The author and Graywolf Press have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify Graywolf Press at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

This publication is made possible, in part, by the voters of Minnesota through a Minnesota State Arts Board Operating Support grant, thanks to a legislative appropriation from the arts and cultural heritage fund, and a grant from the Wells Fargo Foundation. Significant support has also been provided by Target, the McKnight Foundation, the Lannan Foundation, the Amazon Literary Partnership, and other generous contributions from foundations, corporations, and individuals. To these organizations and individuals we offer our heartfelt thanks.

This translation has been published with the financial support of NORLA.

Published by Graywolf Press

250 Third Avenue North, Suite 600

Minneapolis, Minnesota 55401

All rights reserved.

www.graywolfpress.org

Published in the United States of America

ISBN 978-1-55597-784-9

Ebook ISBN 978-1-55597-976-8

2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3 1

First Graywolf Printing, 2017

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017930110

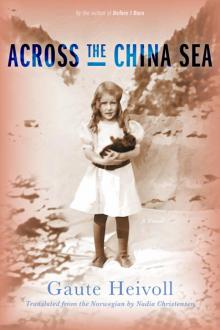

Cover design: Jeenee Lee Design

Cover photo: Augustus E. Martin. Courtesy of the Lenox Library Association. This work is licensed for use under a Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY).

To Anita

ACROSS THE CHINA SEA

PART ONE

1.

In the fall of 1994, while clearing out the house and emptying the writing desk in the living room, I discovered the contract Papa had signed that evening in February 1945. I also found a number of other papers related to caregiving, among them my own letters. There were three photographs of Mama too: one of her standing in front of the Parliament building, another in front of the Royal Palace, and a third beside the bronze lion outside the Kunstnernes Hus art gallery. Except for the pictures, which were tucked inside Mama’s confirmation Bible, everything was in a brown envelope that had been taped shut. On the envelope were the words Caregiving Papers. It was Papa’s handwriting.

The contract had been drawn up by the Stavanger Child Welfare office and signed in duplicate. It stated that Mama and Papa agreed to provide care for five mentally disabled children, for which they would receive eighty kroner a month per child. Perhaps they got the same amount for Josef, Matiassen, and Christian Jensen. I don’t know. Perhaps it was more. After all, they weren’t children.

The document went on to say that Child Welfare would pay for clothing and footwear, as well as for potential doctor visits and medicine.

Furthermore, Papa and Mama promised to:

Provide the children with sufficient, healthy food

Give the children a good, secure place to sleep in their own beds

Keep the children clean and neat

Adapt the children’s work to their ages and abilities

That was all. Four points.

The children’s names and birthdates followed. Lilly. Nils. Erling. Ingrid. Sverre. Sverre was only four years old. There were thirteen years between Sverre and Lilly. She was almost grown up. All had been baptized in St. Johannes parish in Stavanger.

Required termination notice: one month.

The contract was yellowed and full of spots; snowflakes had probably melted on the paper while Papa signed it by the light of Matiassen’s old miner’s lantern. Papa’s shaky signature. The Stavanger Child Welfare stamp. And the date, February 17, 1945.

I remember that it was snowing.

There was a cover letter too. It described the living conditions of the five children before they came to us, and was based largely on a Child Welfare report. The letter was typed on one A4 sheet of paper and attached to the contract with a paper clip. Rust from the paper clip had rubbed off onto the page. The typewritten words were faint and unclear, so I stood by the window to read them.

It was like taking a deep breath.

And then.

The five children had been taken from an apartment in Stavanger near the gata, or street, known as Strandgata on December 22, 1944, after several people had independently expressed concern for the strange, large family. They said you could smell the stench from the apartment the moment you entered the building. So just before Christmas, the Stavanger Child Welfare office sent an inspector to investigate. When he knocked, one of the children opened the door; I imagine it was Ingrid, because the report stated that several of them had inadequately developed language skills. It must have been Ingrid. After all, she had never been able to speak a word. Perhaps she stood in the doorway licking her lips, perhaps she howled softly. Perhaps she made a deep, dignified curtsy the way Lilly had taught her, and stepped aside.

The report was written in ink by a man named Aarrestad. He had knocked on the door and taken off his hat when he entered. Afterward he went home and wrote that during his thirteen years with Stavanger Child Welfare he had never seen anything worse. He was the first to liken them to animals.

Inside the apartment the foul odor was almost unbearable, he wrote. Garbage and trash of every sort, filth, mouse-eaten mattresses, mildewed curtains and newspaper covering the windows. Stinking utter chaos. The man of the house, stonemason Hertinius Olsen, slumped apathetically in a chair while the children crawled around his feet. The children’s mother, Rebekka, stood in a corner of the room, apparently trying to put together a meal, or perhaps she was trying to hide the fact that there was no food in the apartment.

Perhaps she was ashamed.

The report further stated that Hertinius and Rebekka Olsen—who, like their five children, were described as mentally disabled—had not managed to use their ration cards properly. They were no longer capable of providing food, either for themselves or for their flock of children. By the time Aarrestad knocked on the door, they had given up. Aarrestad ended his report with these words: The seven live like animals, under the most ignoble conditions. The children are like animals, with animal habits, and therefore it is recommended that Child Welfare intervene immediately in the case of this poor family.

The children were taken away the following evening.

The weather in Stavanger was calm, cold, and clear. Darkness had fallen, the streets were decorated for Christmas. A few stars shone above the fjord, and there was a thin layer of ice on Lake Breiavannet. The five siblings were driven through the city to the Child Welfare office located at 26 Nygata, not far from St. Petri church. There they were lined up in a row and led through the corridors. They got washed and scrubbed and, at the end, deloused. They were given new clothes, which only partially fit them, but were better than the rags they had before. The two girls got their hair braided, the three boys got a haircut.

No one protested.

On Christmas Eve 1944 they sat for the first time at a table that had been set properly and were served a steaming-hot Christmas meal at Child Welfare expense. Meanwhile, Rebekka and Hertinius Olsen sat alone in the miserable apartment near Strandgata without their five children. Suddenly there was si

lence all around them. No one pestered them for something to eat. No one crawled across the floor making animal-like sounds. Hertinius and Rebekka would never get their children back. I don’t know how they reacted. Perhaps they protested.

The report does not say.

There proved to be no care facility in Rogaland County with the capacity to take in five mentally disabled siblings. It took until late January 1945 before a solution was found. The welfare office contacted care facilities up the coast all the way north to Bergen, along the fjords, and inland across Ryfylke County. But that was before they were told about my parents, both trained as nurses, and about our house in a small parish in southern Norway, forty kilometers from the coast.

After that, everything moved quickly.

The formalities were completed, a contract with four points covering all five children was worked out, and as with the cover letter, everything fit on one page.

I don’t know what the five imagined when they were picked up one morning several weeks later. Maybe they had been told where they were going. Maybe not. Maybe someone told Lilly. She was seventeen years old and perhaps not even mentally disabled, just low IQ; from now on, she would be like a mother for the four other children. Maybe someone told her, maybe she nodded and acted as if she understood.

They had no luggage, no possessions, just the new clothes they were wearing. Lilly gathered the siblings around her, the Child Welfare workers said good-bye, and then the five were led out to the street and into the black car waiting for them.

Rain and sleet showers drifted across the leaden fjord, but when they came to the Jaeren seashore, the weather cleared and they could see how the ocean curved at the horizon.

They drove through Egersund and Flekkefjord, across the Kvinesheia uplands, and at the highest point they could have turned and caught a final glimpse of the sea in the distance.

It was a trip of more than two hundred kilometers.

When they got to Mandal it was already dark. They turned north and continued along the Mandalselva River. The weather grew colder, the snowbanks along the road became higher, and soon they were driving through dark forests; in the searching gleam of the headlights the snow had a bluish glow.

I remember the shimmering headlights that approached from the bottom of the hill, and the car that drove up and turned into the farmyard as I stood with Tone and Josef in the doorway of our house. I remember the moment the driver opened the back door and the first to appear in the light was Lilly. She was eight years older than me, and I thought she was a grown woman. Her hair hung down her back in a long braid; she ducked her head, and stepped out of the car into the snow. She looked like other women I knew, and in the glow of the old miner’s lantern she was almost beautiful. She stood next to Mama, seeming shy and reserved. The two women were the same height. They looked at each other and shook hands, and Lilly curtsied so deeply that her coat spread out on the snow. Then she turned and shouted something into the car, and the siblings got out, one after another; first Nils, then Erling, then Ingrid, and finally little Sverre. At the end they all stood in the snow. It was an odd group, they seemed strange and completely out of place. Nils, who was the second-oldest, but taller than Lilly, wore pants that hung loose at the waist and he pulled them up with his hands in his pockets. He stood beside Mama, grinning, as if someone had just told him an improbable story and he’d almost understood the point. The three youngest children held on to each other: Sverre seemed frightened and clung to Ingrid, who clasped Erling’s hand. Ingrid’s mouth was half-open, as if she were screaming or laughing. But she was doing neither, she was completely quiet. Erling’s head wobbled as he kicked the snow with the tip of his shoe and stole a cautious sidelong glance at Papa. Papa was wearing a winter coat from his years at Dikemark and an old beret. He leaned over the hood of the car and signed the contract on the warm surface. Then he gave a copy of the contract to the driver, and afterward he rubbed his hands together. I saw the snow swirling in the glow of the miner’s lantern.

“Is it them?” Tone whispered.

I nodded.

“It’s them,” I said. “They’re here now.”

I felt a cold draft on my feet. Papa took a few steps forward, and Mama stood next to him in the well-worn sweater Anna had given her. The bluish-white light from the lantern surrounded them like a heavenly glow. It made me think of the wedding picture hanging above the piano in the living room, in which Papa has his hands behind his back and Mama sits in front of him on a chair with her bouquet in her lap to hide the fact that she is pregnant. They are both smiling in the picture. They now stood with their backs to me as the headlights of the stranger’s car lit up the ash tree. I could see a little of the hay barn and the snow-covered fields that gently rose and fell until they disappeared at the edge of the forest. Snow drifted down from the vast, dark heavens. I heard Papa’s voice as he leaned toward Mama and said something only she could hear. And none of us had the slightest idea of what was ahead.

2.

When Papa was twenty years old he left home to become a deacon, a profession that combined nursing and social work. Early one morning he took the “Arendal” train on the long trip from Kristiansand to Oslo, where he went to Diakonhjemmet hospital, which was northwest of the city center at Steinerud, an old estate surrounded by fields, meadows, and oak forests. There he learned to care for patients in a Christlike spirit of love, as they put it. He left home and became a deacon, and that was highly unusual. Hardly anyone left the parish. And certainly not to go to Oslo. If someone left, it was mostly for America, usually in order to earn money or to stay there forever, unless you came back because you had lost your sanity.

Papa was at Steinerud for six months. Then he got a job at Dikemark psychiatric hospital, where he stayed for eleven years. For eleven years he worked with the insane and mentally disabled, and they were eleven good years. At Dikemark there were young boys who howled like wolves at night; there were people who could not walk, sit upright, hold a spoon, or speak; there were older men who believed they were emperors or military commanders, murderers or Christ on the cross. And then there was Eugen Olsen, who was sure that every building where he lived was on fire. Papa loved them all. Working with the insane and mentally disabled was what gave meaning to his life. He had left his rural parish and, for the time being, did not think of going back. The eleven years at Dikemark became the eleven happiest years of his life. I can hear him say it himself: That was when I felt alive.

That was when he felt alive, and it was there, at Dikemark, he met Mama. After several years as a nurse at Ullevål hospital she had successfully applied for a position at Dikemark in the women’s unit, which was separate from the men’s unit but inside the same high fence. The units were reminiscent of venerable manor houses and had names like the Guest House, the Treatment House, the View, and the Castle. From a distance it looked like an old aristocratic estate, with walking paths and a small park. Almost normal, aside from the fence.

Living quarters for the staff were located some distance from the stately treatment units, and it was while walking to and from the night shift that Mama and Papa became acquainted. While they walked beside each other in the dark, she told him about her father, who was the custodian at the Foreign Ministry housing complex on Parkveien, just behind the Royal Palace in Oslo. It was winter, moonlight sparkled on the icy snowbanks along the road, and she told him one of her earliest memories: Uncle Josef standing in the middle of the room in the custodian apartment, singing. They walked together to the staff apartments and lingered awhile in the darkness before unlocking their respective doors. After the next night shift they walked together again. It went on this way until one night Mama stopped at the darkest part of the road. No streetlight. No moon. No stars. Mama stood still, but Papa continued walking for a while before he discovered he was alone. He stopped, turned around, and saw her like a dark shadow, a motion less form darker than the darkness itself.

“Karin?” he said.

&

nbsp; She did not reply.

He walked toward her, but she did not say anything; she just waited until he was very close, and then she put her arms around him.

One of Mama’s earliest memories was of Uncle Josef singing. Later, Josef would be sent to a care facility in Røyken parish, and Mama began to take singing lessons from a woman in the Frogner neighborhood in Oslo. She planned to become a singer—she was encouraged to practice, and told she could go as far as she wished. But when her mother died, Mama stopped abruptly. Instead, she became a nurse. I don’t know what happened. It was as if she suddenly realized that singing had been the wrong track. Better to care for the sick than to sing, to work with the mentally and physically disabled rather than with impresarios. It was as if she suddenly understood.

Perhaps it was Josef who got her to start singing. Perhaps it was because of him that she bought a large, black Steinway concert piano with her inheritance from Grandma, and perhaps it was memories of Uncle Josef that made her think of applying to Dikemark.

Uncle Josef was mentally disabled, after all.

My great-grandfather had been a coach driver at the Granfoss Brug paper mill in Lysaker. People said Josef fell out of the carriage and hit his head, and hadn’t been himself since. He had been talented, no question about that; then he fell, his head struck a rock, and he became a different person. In school he was quickly labeled mentally disabled, but one thing did not change: his deep, resounding singing voice. While still living with his father in Oslo, he sang in the Hope Chorus, which had gone on a concert tour to the city of Trondheim. Exactly where they performed, no one knew for certain. Uncle Josef could not say much about the trip, aside from two memorable events: in Trondheim he met a woman whom he called my young bride, and he saw the midnight sun above Nidaros Cathedral at two o’clock in the afternoon.

Across the China Sea

Across the China Sea